The first time I heard about Golang was a few years back, when the great guys at Brad's Deals, our next door office neighbor organized and hosted the local Go meetup there. Then IO.js and Node.js war broke out and TJ Holowaychuck shifted from Node.js to Golang announcing the move in an open letter to the community.

I did not think much of the language, as its reputation was far from the beauty of a real functional language.

Fast forward a couple of years and I am giving Ruby a serious try on AWS Lambda. Ruby works there, however, it needs enough memory and 3000 ms (3 seconds) to do anything. We have to invoke some of them millions of times in a month and when we calculated the cost for it, the bill gets fairly large quickly.

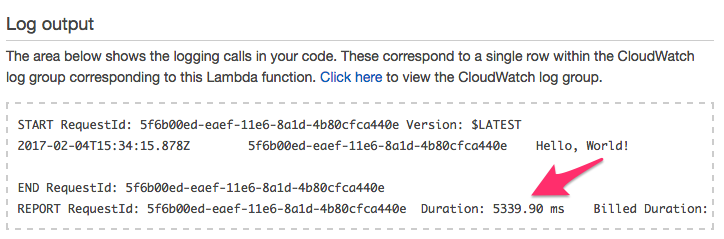

I created a simple AWS Lambda with Ruby just to print the words "Hello, World!" with 128 MB memory. It took 5339 ms to execute it.

Then one night I wrote a tiny Go program:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

fmt.Println("Hello, World!")

}

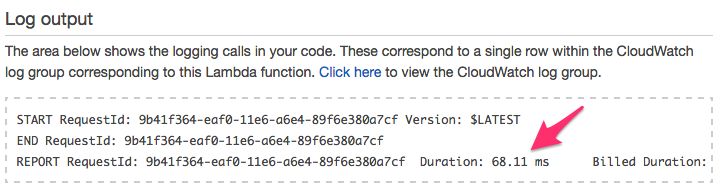

I cross compiled (since I am working on OSX) with the command GOOS=linux GOARCH=amd64 go build github.com/adomokos/hello to Linux, packaged it up with a Node.JS executor and ran it. I couldn't believe my eyes, it took only 68 ms to get the string "Hello, World!" back. 68 ms! And it was on a 128 MB memory instance. It was beautiful!

Ruby would need four times the memory and it would still execute ~10 times slower than Go. That was the moment when I got hooked.

Go is a simple language. I am not saying it's easy to learn, it's subjective: it depends on your background, your experience. But it's far from the beauty of Haskell or Clojure. However, the team I am working with would have no trouble switching between Go and Ruby multiple times a day.

What kind of a language today does not have map or reduce functions?! Especially when functions are first-class citizens in the language. It turns out, I can write my own map function if I need to:

package collections

import (

"github.com/stretchr/testify/assert"

"strconv"

"testing"

)

func fmap(f func(int) string, numbers []int) []string {

items := make([]string, len(numbers))

for i, item := range numbers {

items[i] = f(item)

}

return items

}

func TestFMap(t *testing.T) {

numbers := []int{1, 2, 3}

result := fmap(func(item int) string { return strconv.Itoa(item) }, numbers)

assert.Equal(t, []string{"1", "2", "3"}, result)

}

Writing map with recursion would be more elegant, but it's not as performant as using a slice with defined length that does not have to grow during the operation.

History

Go was created by some very smart people at Google, I wanted to understand their decision to keep a language this pure.

Google has a large amount of code in C and C++, however, those languages are far from modern concepts, like parallel execution and web programming to name a few. Those languages were created in the 60s and 80s, well before the era of multi-core processors and the Internet. Compiling a massive codebase in C++ can easily take hour(s), and while they were waiting for compilation, the idea of a fast compiling, simple, modern language idea was born. Go does not aim to be shiny and nice, no, its designers kept it:

- to be simple and easy to learn

- to compile fast

- to run fast

- to make parallel processing easy

Google hires massive number of fresh CS graduates each year with some C++ and Java programming experience, these engineers can feel right at home with Go, where the syntax and concept is similar to those languages.

Tooling

Go comes with many built-in tools, like code formatting and benchmarking to name the few. In fact I set up Vim Go that leverages many of those tools for me. I can run, test code with only a couple of keystrokes.

Let's see how performant the procedure I wrote above is. But before I do that I'll introduce another function where the slice's length is not pre-determined at the beginning of the operation, this way it has to auto-scale internally.

func fmapAutoScale(f func(int) string, numbers []int) []string {

// Initialize a slice with default length, it will auto-scale

var items []string

for _, item := range numbers {

items = append(items, f(item))

}

return items

}

The function is doing the same as fmap, similar test should verify the logic.

I added two benchmark tests to cover these functions:

// Run benchmark with this command

// go test -v fmap_test.go -run="none" -benchtime="3s" -bench="BenchmarkFmap"

// -benchmem

func BenchmarkFmap(b *testing.B) {

b.ResetTimer()

numbers := []int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10}

for i := 0; i < b.N; i++ {

fmap(func(item int) string { return strconv.Itoa(item) }, numbers)

}

}

func BenchmarkFmapAutoScale(b *testing.B) {

b.ResetTimer()

numbers := []int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10}

for i := 0; i < b.N; i++ {

fmapAutoScale(func(item int) string { return strconv.Itoa(item) },

numbers)

}

}

When I ran the benchmark tests, this is the result I received:

% go test -v fmap_test.go -run="none" -benchtime="3s" -bench="BenchmarkFmap"

-benchmem

BenchmarkFmap-4 ‡ 10000000 | 485 ns/op | 172 B/op | 11 allocs/op

BenchmarkFmapAS-4 ‡ 5000000 | 851 ns/op | 508 B/op | 15 allocs/op

PASS

ok command-line-arguments 10.476s

The first function, where I set the slice size to the exact size is more performant than the second one, where I just initialize the slice and let it autoscale. The ns/op displays the execution length per operation in nanoseconds. The B/op output describes the bytes it uses per operation. The last column describes how many memory allocations it uses per operation. The difference is insignificant, but you can see how this can become very useful as you try writing performant code.

Popularity

Go is getting popular. In fact, very popular. It was TIOBE's "Language of the Year" gaining 2.16% in one year. I am sure you'll be seeing articles about Go more and more. Check it out if you haven't done it yet, as the chance of finding a project or job that uses Go is increasing every day.